“Keep telling my story,” Abe Piasek, a Holocaust survivor, told his friend Steve Goldberg, a Triangle school teacher, in January 2020, shortly before he died. It was a charge Goldberg would take to heart in ways that sometimes seem surprising even to himself.

Piasek was 91 years old and under hospice care. He and Goldberg had met two years earlier when Goldberg, then a U.S. history teacher at Research Triangle High School, introduced Piasek as a speaker to four classes of students in the school’s black box theater. Piasek spoke to the students for 45 minutes each, and made an impression on them—and on Goldberg.

Piasek had been speaking to communities across the state after moving to North Carolina in 2009, and Goldberg had looked him up and sent information out to the school community about him; the school principal asked Goldberg to introduce Piasek to the students as a speaker.

“I just was taken by his personality, his energy,” Goldberg recalls of meeting Piasek for the first time. “There was something about him reminding me a little bit of my grandfather.”

Feeling that 45 minutes wasn’t enough time to fully understand his life story, Goldberg interviewed Piasek at his home in Raleigh, where they spoke for more than two hours.

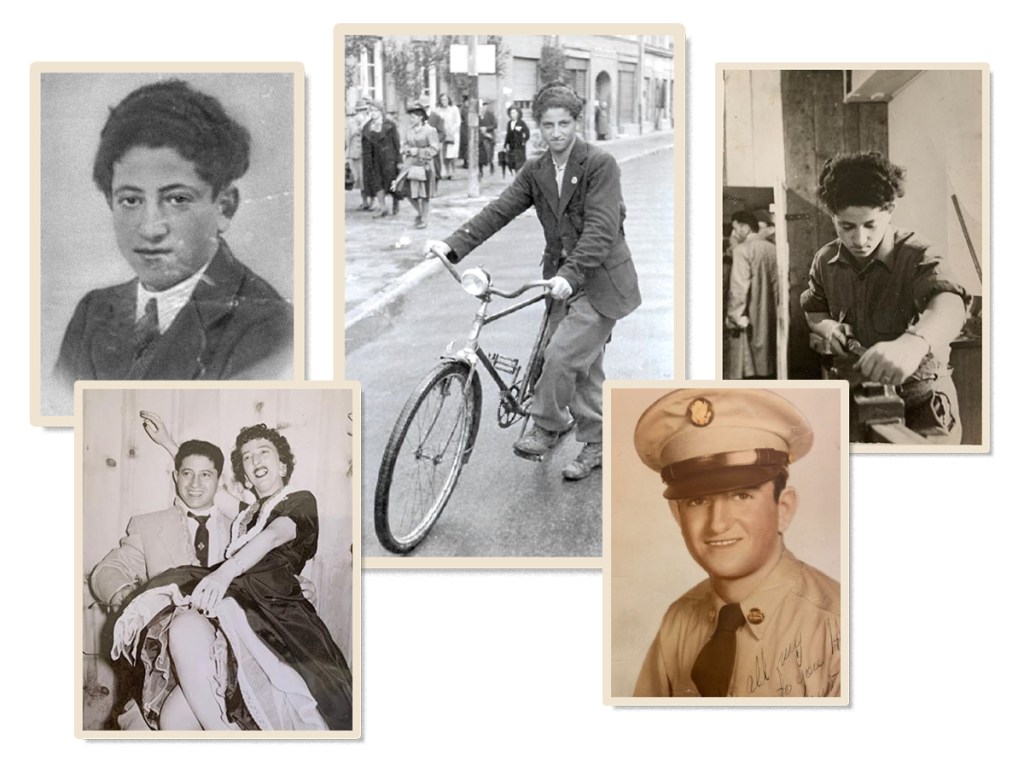

Piasek told Goldberg about his life in Bialobrzegi, Poland where he lived with his parents and younger sister. He was 11 when the Nazis invaded, and 13 when he was separated from his family. He never saw them again. Piasek worked in three slave camps from 1942 to 1945, including Auschwitz in 1944.

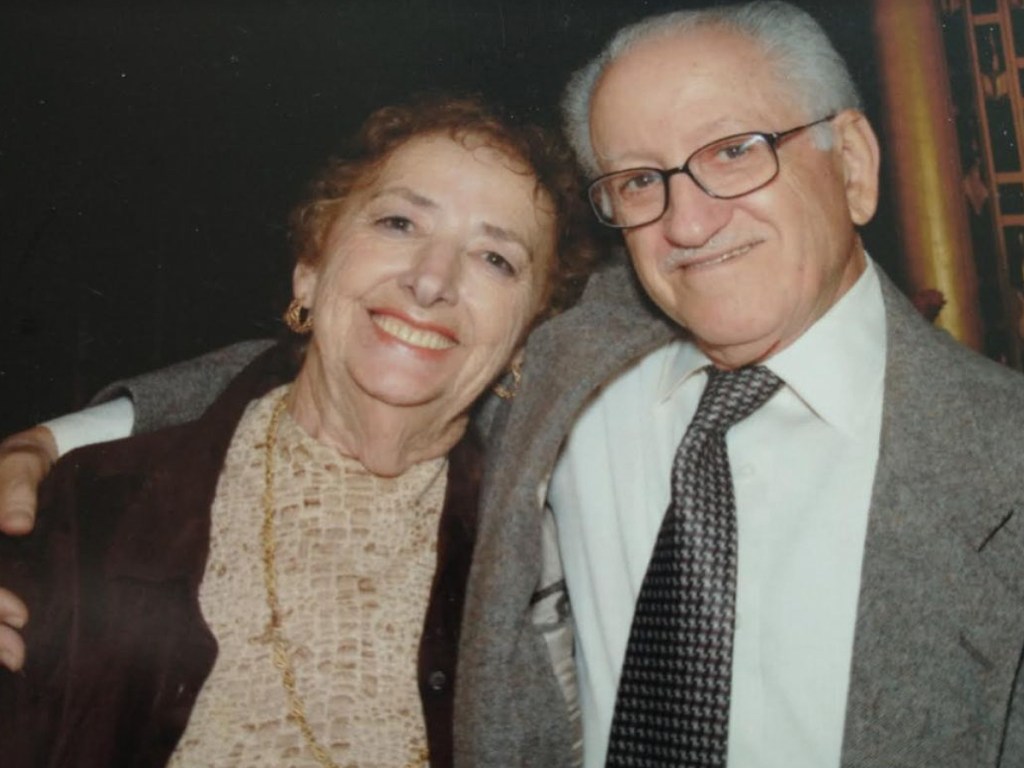

Piasek was liberated from a cattle car in April 1945, at age 16, and came to the United States in 1947. He worked as a baker and lived in Connecticut, California, Florida, and finally, North Carolina, where he moved with his wife, Shirley, to be close to his daughter, Pam (Piasek also has a son, Joe, who lives in New York). It wasn’t until much later in his life that Piasek began talking about his experience during the Holocaust, after agreeing to an interview with the Shoah Foundation.

On the day they spoke at Piasek’s house, Goldberg mentioned he was traveling with his class to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Piasek, who had never visited the museum before, offered to accompany the students, and two of his own great granddaughters, on the trip. At the museum, Piasek wanted to see a cattle car on exhibit on the third floor; when he got there, he stood in the cattle car and narrated his liberation from a similar container decades earlier.

“I was getting chills,” Goldberg recalls. “Imagine going to a place where it’s totally evocative, in smell and look and feel, of a place where you had unbelievable trauma when you were 15, 16 years old. That’s what he did. And he did that so the students and his great granddaughters would have this experience that they’re never going to forget.”

Piasek had a knack for connecting with the students he spoke to, Goldberg says. He never used notes and spoke from memory, reading the audience and speaking in ways that drew them in. Often, he was one of the students’ first introductions to the history of the Holocaust, a warm, captivating speaker with a powerful story who commanded their attention and inspired them to ask questions. There never seemed to be enough time to answer them all.

As a teacher himself, Goldberg feels that those constraints—on Piasek’s speaking time and on teachers more generally who are tasked with teaching such a significant period in modern history—are unfortunate. Goldberg wants to do justice to Piasek’s story and his legacy, and says he realized the best way to do that was to keep Piasek the main focus.

Now, Goldberg travels around the state telling Piasek’s story at schools and libraries, synagogues and community centers, companies, colleges, and universities. He uses the elements of Piasek’s own storytelling, plus video clips of Piasek himself, to forge the same connections Piasek made with his listeners. Students have sent Goldberg letters after his talks and Piasek’s story has inspired art and other student projects.

Telling Piasek’s story, Goldberg says, has become his full-time job, and he’s shared it 145 times, with nearly 8,000 people so far. He’s also working on a book about the work he’s been doing.

This year marked the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, and it’s not lost on Goldberg that, soon, there won’t be any Holocaust survivors still living. Second and third generation descendants of Holocaust survivors are organizing to tell their stories, and Goldberg hopes that, in addition to their efforts, his work can be another model for how that history is preserved and that young people, especially, could learn about the Holocaust through Piasek’s experience.

Goldberg also recognizes the precariousness of the times that we’re living through. Piasek had a simple message—“don’t hate”—but Goldberg takes it further.

“There are a lot of parallels between the events that led to the Holocaust and the rise in antisemitism, and you’re seeing a rise of authoritarian regimes that are not respecting human rights [today],” Goldberg says. “And so it feels like this is a moment when Abe’s story really matters.”

This week marks Yom HaShoah, a day dedicated to Holocaust remembrance. Goldberg will speak at the Chapel Hill Library on April 22, at Durham’s Beth El Synagogue April 23, and to students at Cary Academy on April 24.

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle. Follow Raleigh Editor Jane Porter on X or send an email to [email protected].