In the middle of the night on July 6, as Tropical Storm Chantal unleashed on Chapel Hill, Lou Horton and her husband Paul Greganti huddled in their attic with their three cats.

The couple’s one-story house is not positioned well for such an event. It sits in a hollow where the land drops sharply away from Fordham Boulevard, accessible only by driving down what is essentially a steep driveway off that road. You can barely see their rooftop from the street.

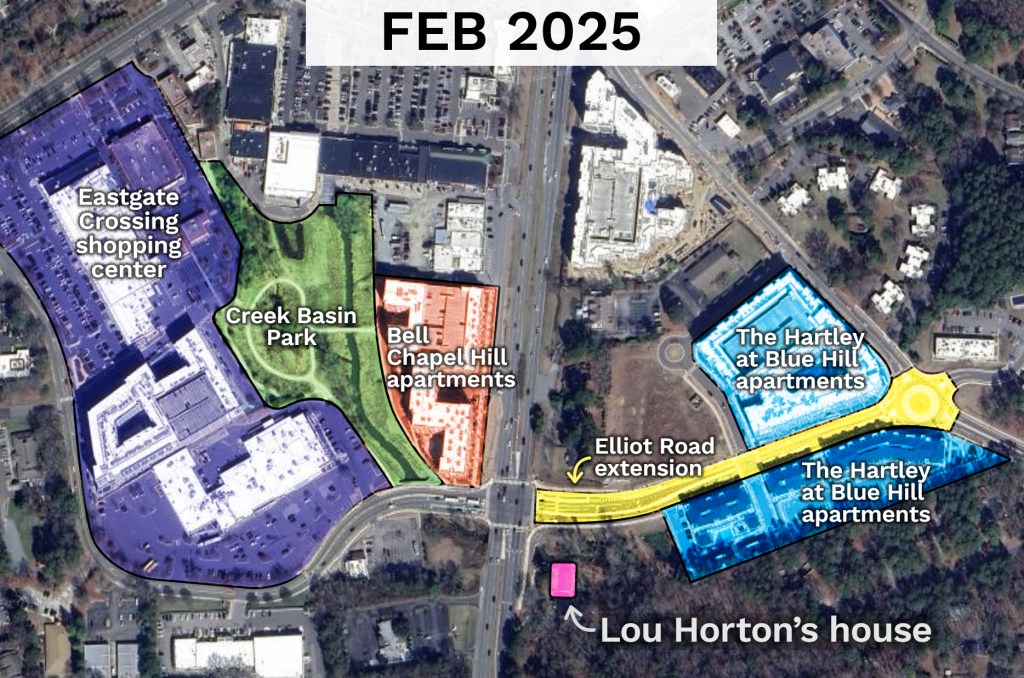

Their house also sits on the banks of Booker Creek, a half-mile downstream from Eastgate Shopping Center.

The night of Chantal, the creek became a conveyor belt for debris from Aldi, Dollar Tree, and other Eastgate businesses. From their attic, Horton and Greganti could hear but not see what was rushing past in the darkness.

“That was the scariest part,” Horton says. “We heard things flowing by and smashing against the house. Anything that flowed by could’ve been a dumpster or a tree or a telephone pole crashing into our house and killing us.”

For Horton and Greganti, the flood was both a singular catastrophe and the culmination of years spent watching their situation become more precarious. Trapped in a house no one else will buy, watching new apartment complexes spread upstream while their own land erodes into the creek, they’re part of a growing class of people stuck in homes increasingly threatened by natural disasters—climate refugees who haven’t yet left.

Earlier that day, around 4 p.m., Horton had moved her car to higher ground behind Squid’s Restaurant and pressed Greganti to do the same with his truck. Flash flood warnings had been pinging her phone all day.

Greganti declined, saying his truck was out of gas. The house, made of cinderblocks cinder blocks in 1952, had never flooded inside in the 22 years since he bought it. He’d been watching the radar all day and was convinced they’d be fine.

Horton offered him $40 for gas to move his truck. He said no. She gave up and fell asleep, weary from working her jewelry booth at the Festival for the Eno all weekend.

Greganti woke her up a few hours later, at 8:10 p.m.

“It’s flooding,” he said. He’d already moved his truck and hoisted the lawnmower onto the porch.

Horton watched out the window as water crept up the side of the house. When it rose to less than a foot from the sill, she rolled down the shades.

“I was starting to get seasick,” Horton says.

She called her brother.

“I was like, ‘Yeah, so, I’m gonna die. I’m probably gonna die,’” Horton recalls telling him.

He urged her to call 911. She tried. No one answered. The emergency system was overwhelmed with nearly 8,000 calls that night, according to Alex Carrasquillo, communications manager for the Town of Chapel Hill.

Horton and Greganti moved to the attic soon after. The smell of gasoline, from their lawnmower that had washed off the porch, filled the air as the hours passed. Around midnight, Greganti’s phone rang. Horton answered. It was a first responder.

“Are you in your house?” the first responder asked. “We’re coming to rescue you.”

“You have to rescue our neighbors first,” Horton responded. Horton and Greganti share Bypass Lane with just one other household—an elderly couple who lives with their three adult children, according to Horton.

The responder assured Horton they were talking to the neighbors’ son; that’s how they’d known to call Greganti. “We’re coming to get you,” the first responder said. “We just have to get a boat here.”

But the rescue never materialized. No one came to get them, and they didn’t receive another call.

The water receded around 1:30 a.m. At its height, it had reached two feet inside their house. Horton and Greganti climbed down from the attic and met their neighbors in the middle of what remained of their shared driveway, comparing notes.

The neighbors hadn’t even realized Horton and Greganti were home. The adult children had gone to move their cars soon after Greganti did and by the time they returned to the intersection of Bypass and Fordham, they couldn’t make it back through the floodwaters, according to Horton. After hours waiting by the side of the road, they’d been spotted by Chapel Hill police, who called for a water rescue upon learning their parents were trapped inside. But the boat the first responders brought had no motor, and they determined the water was moving too quickly to use it.

Carrasquillo confirmed the attempted rescue to the INDY, writing that firefighters had tried to perform a rescue but “could not safely do so in the fast-moving water.”

In the immediate aftermath of the flood, Horton and Greganti have been displaced and nearly all of their belongings destroyed. Greganti has FEMA flood insurance, but it currently only covers the structure, not personal property.

Horton’s livelihood is also on indefinite hiatus. She makes money selling handmade copper jewelry and renting out a kiln in her backyard. The night of the flood, her shed full of jewelry supplies floated 200 feet before crashing into a neighbor’s car. Her packaging and shipping materials were swept away. Over a month later, the kiln is still airing out.

Greganti is disabled and not currently working; Horton provides their only income. With scant savings to cushion the blow, they’re scrambling to figure out what comes next.

But the long-term reality is harder to confront. The couple knows another flood like this will come. And they have nowhere to go.

Horton happens to be the great-granddaughter of the dairy farmers who once owned the swampy land where Eastgate Shopping Center was built in 1958. That has nothing to do with the fact that she lives right next to it.

“I did not inherit anything,” she wrote in an email to the INDY. “I’m a millennial, I’m poor as shit.”

The house where she and Greganti live sits in a FEMA-designated floodway—Zone AE, the highest-risk flood zone where water naturally flows during major flood events. This designation was not in place when Greganti purchased the property for $121,000 in 2003, drawn by its affordability and natural setting on just under a half-acre. At the time, it was designated generally as being in a 100-year floodplain.

“The meaning was unclear but not something that seemed threatening or devastating,” Horton says.

Over the years, they’d experienced some flooding in the crawlspace but nothing that threatened the living space of the house. In October 2018, FEMA updated its maps, officially designating their property as part of the floodway.

That 1,000-year storm? It’s not gonna be another 1,000 years before it shows up again.

professor danielle spurlock

Unrelated to the new FEMA designation, Horton and Greganti put their house on the market that year. Major changes were coming to the area surrounding Bypass Lane after a 180-acre site, known as the Blue Hill District, had been rezoned in 2014 to encourage dense, mixed-use development, and Horton was growing worried the development would increase the risk of flooding. They left the house on the market for two years. There were no takers.

Then came the wave of new development. In 2021, Chapel Hill began construction on the Elliott Road Extension, a project that would connect South Elliott Road to Ephesus Church Road, cutting through the middle of Bypass Lane. The stated goal of the extension was to improve connectivity within the Blue Hill District, envisioned to be a walkable “live-work-play” environment.

Around the same time, new apartments began sprouting up throughout the district. Straight up the hill from Horton and Greganti’s backyard, The Hartley at Blue Hill—414 luxury apartments across 12 buildings, plus a 500-space parking deck—replaced The Park at Chapel Hill, a much smaller complex that had offered some of the town’s last naturally affordable housing. Across the street, Ram Realty began construction on Bell Chapel Hill, a 273-unit complex that would reduce an area where water naturally collected by 20 percent.

As part of accommodating the new development, the town poured money into stormwater improvements, including a $1.1 million project to expand the floodplain between Eastgate and South Elliott Road, creating more space to hold water during storms.

The Blue Hill District’s stormwater infrastructure is rated for 100-year storm events: storms that statistically have a 1 percent chance of occurring in a given year. Chantal—a 500- to 1,000-year storm, per meteorologists—overwhelmed its capacity.

But these classifications—technical terms based on historical data—increasingly fail to capture the new climate reality. Danielle Spurlock, a UNC professor specializing in land use and environmental planning, says this mismatch between infrastructure design and extreme weather is becoming the norm.

“In this case, I would say [the town] did the most they could do, but because of climate change, it’s not gonna be enough,” Spurlock says. “That 1,000-year storm? It’s not gonna be another 1,000 years before it shows up again.”

Spurlock adds that municipalities typically approach stormwater management parcel by parcel rather than thinking cumulatively about watershed impact. Even when developers follow all the rules, the collective effect of more impervious surfaces can overwhelm downstream areas during extreme weather events, she says.

When asked about the impact of the town’s development decisions on flooding at Bypass Lane, Carrasquillo wrote in an email that “6 and 7 Bypass Lane are entirely within the floodway which is the highest chance area for flooding and this was a historic storm in our community.” The Elliott Road Extension “was designed and built to meet all applicable stormwater ordinances,” Carrasquillo wrote, and all projects in the Blue Hill District “are required to build stormwater systems that manage some of the pre-existing impervious surface on the site.”

From where Horton stands—on increasingly eroding banks—the technical compliance means little.

“I can’t live here,” she says. “It’s ruined. There’s nothing I can personally do to make this land safe.”

Parsing the impacts of a historic storm from those of upstream development isn’t straightforward. It’s clear from aerial imagery that there are significantly more impervious surfaces and fewer trees in the watershed. It’s harder to say how severe the flooding the night of July 6 would have been without those changes.

What’s certain is that storms are getting worse and the people who can least afford to relocate are trapped in harm’s way.

“We have done so little to protect the individual homeowner within the system,” Spurlock says. “We’ve depended on these very ecologically vulnerable areas to provide affordable housing.”

The system, she adds, “is acting according to its design. The design was going to place them at risk, and we placed them at risk. We said that’s a risk we’re okay with—that’s on that individual homeowner. And we don’t give them a pathway out.”

Nine days after Tropical Storm Chantal, ten volunteers from the disaster relief group Baptists on Mission make an hour-drive from Thomasville to Bypass Lane.

Horton and Greganti aren’t home. They’ve been staying with Greganti’s sister in Raleigh. Earlier in the week, Horton had seen a flyer at a disaster relief center in Carrboro and registered her address. She figures this is how the Baptists on Mission knew to come.

The volunteers gather in a circle and join hands to pray before getting started. Then they get to work. The crew’s leader, Adrienne Cromer, has a no-nonsense attitude and a brisk benevolence about her. She does a walkthrough of the house alone first, then waves the others in.

“There’s gonna be mold growing under these floors,” Cromer says. “I can smell it.”

Outside, Horton and Greganti’s belongings lay scattered across the yard, waterlogged and sticky from the humidity: lamps and wooden furniture; metalworking tools, sketchbooks, and balls of yarn; an ironing board; baking pans. Pants and shirts lay flat on the grass like a rapture scene.

“Anything that looks artsy goes right here,” one volunteer calls out, carefully placing a piece of Horton’s copper jewelry into a plastic bin.

Around the side of the house, the banks of the creek are piled high with fallen branches and garbage from Eastgate. It looks like someone TP’d the trees with plastic shopping bags.

I can’t live here. It’s ruined. There’s nothing I can personally do to make this land safe.

lou horton

During the flood, six dumpsters floated past Horton and Greganti’s house, Horton says. OWASA crews came a few days later to haul them away—as well as an additional one that had lodged against a culvert under Fordham Boulevard.

The Baptists on Mission work into the afternoon, hauling bigger items from the house—a piano, an organ, a furniture set Horton had recently inherited from her grandmother—and piling them into a dump trailer Horton borrowed from a friend. The next day, Horton’s dad drove the trailer to a landfill and paid $56 to dispose of it.

Horton can’t see any reliable way to prepare her property—or herself—for the next big storm.

She’s attempted some DIY erosion control over the past few years, but the flood tore up the dogwood tree, gardenia bush, and weeds she’d been trying to cultivate to hold the eroding bank. The larger trees that remain present their own dilemma—Horton and Greganti fear them falling on their house, but cutting them down would accelerate the erosion further.

She’s looking into expanding their flood insurance to cover personal property, but that takes time and money they don’t have right now and also feels somewhat futile: Insurance won’t bring them back to life if they drown in the next storm.

When it comes to their physical safety, the only protection is knowing when to evacuate, but official systems offer limited help, Horton says. Flash flood warnings are sent out constantly for their area; Horton and Greganti aren’t going to evacuate for all of them.

And while Orange County issues evacuation orders through its OC Alerts system during predictable floods, flash flooding presents unique challenges, according to Wil Glenn, Orange County’s Community Relations Director.

“Unlike a riverine flooding scenario or dam failure where a river floods out of its banks in a predictable fashion, flash flooding is nearly impossible to predict with the accuracy necessary to affect a coordinated evacuation,” Glenn wrote in an email to the INDY.

Ahead of Chantal, the county issued a voluntary evacuation notice for communities within the inundation area of the Lake Michael Dam. But by the time the need for evacuation in other areas became clear, it was too late to issue a mass order, as “sending a general notice to evacuate without context of the safe routes could have potentially made the situation worse by putting residents on flooded roads,” Glenn wrote.

With no reliable early warning system, Horton says she’s found herself grasping at anything that might offer guidance. The night of the storm, she’d even half-wondered if the full moon might make things worse—something about the tides, she reasoned.

“We have to read the tea leaves and say, ‘Hey, do you think it’s going to flood?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Should we move our cars?’ ‘I don’t know,” she says. “This is how broken it is. It’s like, why don’t I just deal myself a little tarot spread?’”

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify the timing of Horton’s phone call to her brother and add additional details from her experience on July 6. A previous version incorrectly described the Elliott Road Extension as cutting 6 and 7 Bypass Lane off from the rest of the street.

Follow Staff Writer Lena Geller on Bluesky or email [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected]