The volunteers meet inside a Carrboro coffee shop on a muggy late-July afternoon.

All three are self-described introverts, which makes the door-to-door effort they’re about to embark on—recruiting businesses for ICE defense training—a bit daunting, even for Ashley Trudeau, the one experienced volunteer.

Trudeau spreads her toolkit across the table to show the two newbies the materials they’ll use for canvassing.

“I really like this one and I lean on it a lot,” she says, pointing to a half-sheet titled “IF A FEDERAL AGENT ENTERS” with steps to take: Ask agents to identify themselves. Ask if they have a judicial warrant. Film the interaction. And so on.

The goal of the canvas is to get local businesses to become “Fourth Amendment Workplaces.” In the simplest sense, that means getting owners to commit to informing their staff of what the Fourth Amendment is—protection against unreasonable searches and seizures—and having a game plan in the event that federal agents show up to conduct workplace raids.

When businesses look at that “IF A FEDERAL AGENT ENTERS” sheet, Trudeau says, they often realize they aren’t prepared.

Over the next hour, the volunteers visit 11 businesses along Carrboro’s main drag. At most places, decision-makers aren’t around, but staff are appreciative of the effort and agree to pass information to their managers. An employee at a gift shop says he’s eager to have a more concrete protocol in place.

“At this point I’m literally just going to throw stuff at them and run into the back room and lock it,” he says of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents hypothetically showing up.

Just one business owner is present in his establishment during the canvass. He agrees to sign on, but only after Trudeau explains that there’s an option to go on the “quiet list,” meaning his business will receive training and information but won’t be publicly identified as a participant.

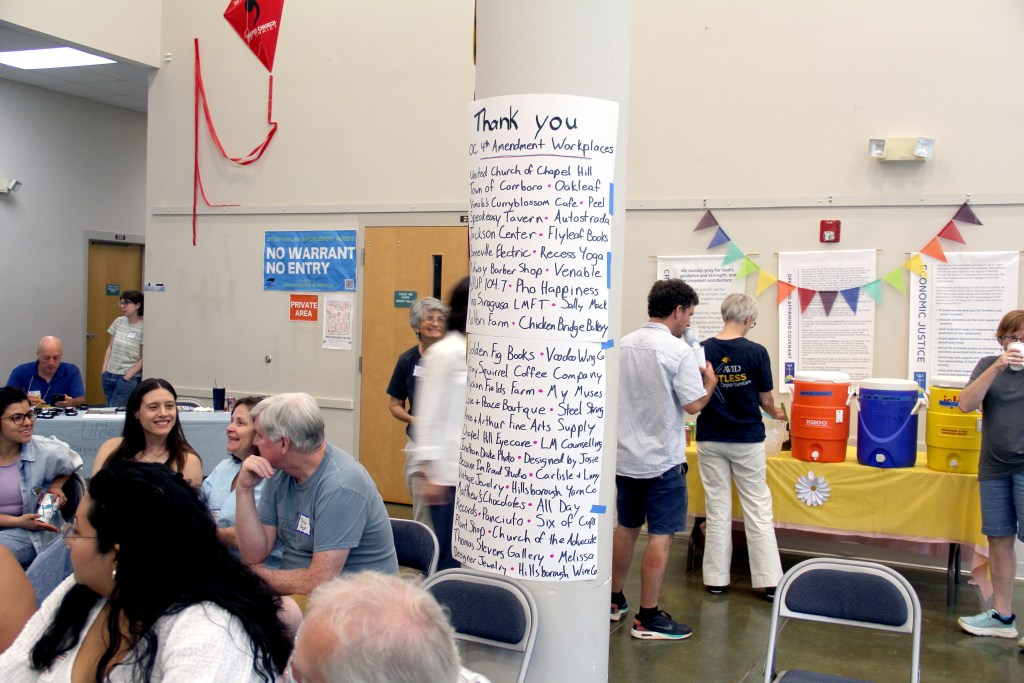

The moment highlights the dual strategy of the Fourth Amendment Workplace initiative, which the immigrant rights organization Siembra NC launched in April. Part of the approach relies on visible community support as a deterrent to raids on workplaces. Over 200 businesses statewide have signed on, most publicly. Orange County has 43 participating workplaces. Durham and Guilford Counties have dozens more. Even businesses in redder counties like Johnston have joined. Siembra strategically began by recruiting established businesses that don’t employ many immigrants to create a protective buffer for more at-risk workplaces, says organizer Andrew Willis Garcés.

“We think that the most vulnerable workplaces are going to be less likely to be targeted if there are high-profile, high foot traffic businesses saying the Fourth Amendment is important,” Willis Garcés says.

But the practical applications of the initiative are equally crucial, which is why the second strategy of participating quietly is still valuable. Siembra has documented three workplace raids in North Carolina this year, including a major raid at Buckeye Fire Equipment in Kings Mountain in June that led to 30 arrests. ICE arrests statewide are up 170 percent. And Willis Garcés sees the threat extending far beyond immigrant communities.

“I think a thing that we’ve learned from the last couple of years is, solidarity isn’t enough,” Willis Garcés says. “With Project 2025, and Trump’s campaign pledges at his rallies, he basically said he was going to find a way to target all kinds of Americans. How he would target immigrants was the headline most of the time, but the blueprint is there, and we’re seeing it now, how he would dismantle protections for all kinds of people. So we think it’s important that basically that is matched with the number of people organizing in collective self defense.”

When businesses sign on to become Fourth Amendment Workplaces, volunteers from Siembra conduct on-site trainings that involve a range of preparations: role-playing encounters where employees practice asking agents to identify themselves while someone films; walking through the space to designate which areas are “private” (break rooms, offices, anywhere marked “Employees Only”) since ICE needs a judicial warrant to enter those zones but not public areas; and examining sample warrants to spot the difference between administrative ones that ICE issues to itself and judicial ones signed by a judge.

“If they want to do something illegal, they will,” Trudeau says, of ICE, while pitching the initiative to an employee in a Carrboro hair salon. “But they’re also using psychological terrorism. Knowing what we’re allowed to do, and not making it easy for them, can help.”

At the United Church of Chapel Hill on an August afternoon, traditional dancers in feathered headdresses perform for a crowd gathered around tables with colorful tablecloths. They kick their legs and spin to the beat of a drum while attendees—volunteers, business owners, local electeds, and Siembra organizers—occasionally break away to the buffet table, where aluminum trays of tacos are steadily depleting alongside bowls of red and green salsa labeled “mild” and “hot.”

The gathering is meant to celebrate both local success and national momentum tied to the Fourth Amendment Workplace initiative, which is now being adapted and implemented in 14 other states. In Oregon, organizers have formed a “Baddies for the 4th” group; in Ohio, the City of Cleveland Heights is preparing to pass a resolution proclaiming itself a Fourth Amendment Workplace.

The Town of Carrboro passed its own such resolution in May. Durham is expected to follow suit on Monday.

After the dance performance, a series of speakers take the microphone to tout milestones of the initiative, and there’s something slightly disorienting about celebrating a credentialing system that was invented four months ago and hasn’t yet been tested in a real ICE encounter. But beneath the novelty, there’s a subtext: no mode of resistance that already existed felt adequate or accessible. The traditional playbook—donating to Democrats, posting on social media—is part of the machinery that led to this moment. Siembra’s approach works outside those channels, building power through direct action and hyperlocal community building that doesn’t depend on institutions to save anyone.

“I feel really strongly about just being able to stand up and do something right now,” says Brad Bonneville, whose electrical contracting company joined the Fourth Amendment initiative in the spring. “I’ve been kind of waiting for this whole debacle to unfold most of my life, as things have moved in this direction, with the climate and with politics. And now that it’s happening, it’s like, feeling totally unprepared.”

Part of the celebration’s stated intent is to infuse joy into resistance work as a counter to the fear gripping local communities.

“No papers, no fear, the community is organizing here,” raps Marco Cervantes, an organizer.

“You don’t actually have to be scared of despots,” says Carrboro town council member Cristóbal Palmer, adding that his grandfather fled Poland in 1938 and later fled Peru when it turned autocratic. “Historically, looking around the world, they actually end up being quite fragile because they have to be paranoid. So we need to just stand together, find our community, and we will get through this.”

But the buoyant mood is fraught with underlying tensions. Bonneville, the electrician, is shaking as he speaks. His employees all have their paperwork, he says, but their friends and families might not. If he becomes a target, he worries ICE could come after them. He’s caught between contradictory fears: the “fear of spending my life knowing that I hadn’t spoken up during a time of sea change when our rights are being rescinded,” he says, reading from notes he’s scribbled down. “And the fear of what happens if I do speak out.”

The next phase of the Fourth Amendment Workplace initiative involves putting pressure on municipalities to help scale the program. The Town of Carrboro has begun setting up workshops for businesses through its economic development office, which has relationships with all 600 businesses in town.

On the ground, volunteers are still figuring out the best approach—whether door-to-door canvassing or word-of-mouth and personal relationships yield better results.

During the July canvass, even though employees were enthusiastic, it seemed unlikely that any of them would follow up, as goes cold outreach. “I always wash business cards,” one coffee shop employee told the group, then asked them to write information down on a scrap of paper, which seemed even less promising.

But sometimes the combination of grassroots effort and personal connections pays off. One of the businesses the group canvassed did follow up—Speakeasy, a bar on Weaver Street. As it turned out, one of the newbie volunteers had gone to grad school with the owner, Nona Poulton, which helped bridge the gap between interest and commitment.

Speakeasy just completed its training this week. Poulton, who’s also a nurse practitioner, says she views the Fourth Amendment Workplace initiative as something akin to herd immunity.

“Am I worried about our workers in our business? Not at the moment,” she says. “Not currently. But I can’t say that that won’t change.”

Follow Staff Writer Lena Geller on Bluesky or email [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected]