Early in this year’s hurricane season—if such a designation still exists, given the increase in frequency and severity of storms—Tropical Storm Chantal swept into central North Carolina with devastating, record-setting rainfall.

Four counties—Alamance, Chatham, Orange, and Moore—declared states of emergency, and at least six people died in storm-related deaths. The seemingly relentless rain fell fast, saturating some areas with nearly 12 inches of water in 24 hours. The Eno and the Haw both rose to levels not seen since 1996’s Hurricane Fran.

In Saxapahaw, a revitalized mill town of about 1,300 people, Caitlyn Swett, like many of her neighbors, watched the Haw River’s rising waters through the night. At the time, she lived in the Rivermill Apartments, a renovated former cotton mill that consists of two big buildings, one a former spinning mill, the other a dyehouse, both of which are located on the river’s banks. With the water rising, a tall friend evacuated her by piggyback through floodwaters that were already waist-high for him.

A dancer and sound artist, Swett is the managing and development director at Culture Mill, a performing arts organization that has been part of the Saxapahaw community since the nonprofit was founded in 2017. The Culture Mill Lab, located across the street, was on higher ground than her apartment, so Swett went there with other evacuees, texting updates on the storm to friends and colleagues.

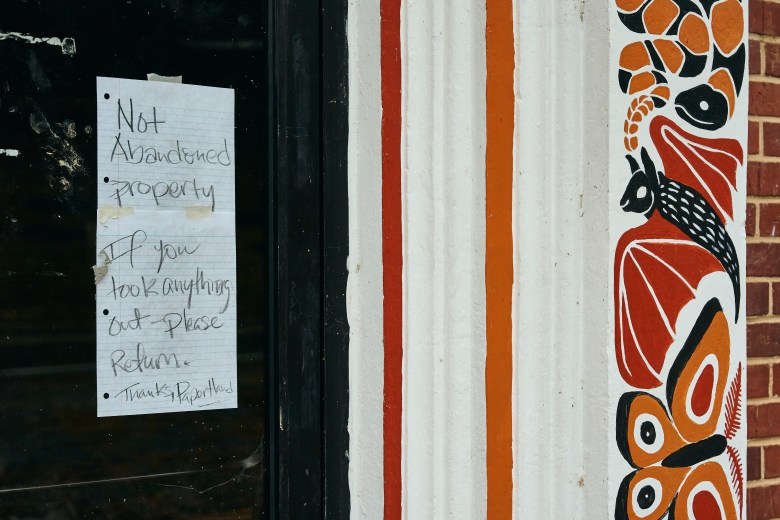

One of those friends was Lea Clayton, whose partner is Paperhand Puppet Project’s executive director and co-founder Donovan Zimmerman. From her vantage point, Swett could see Paperhand’s studio, which lies even closer to the river’s edge than Swett’s mill apartment. “I called and told them the river was rising, and they said, ‘Let us know if it reaches the door,’” said Swett.

I texted them a picture and said, ‘I’m so sorry, it reached the door,’ which meant water was in their space.”

caitlyn swett

“I texted them a picture and said, ‘I’m so sorry, it reached the door,’ which meant water was in their space.”

By the time Zimmerman arrived, the river had crested and the waters began to recede. People were already at the studio, moving wet puppets out of the mud and into the parking lot, hoping they’d dry in the sun. Made of papier-mâché, cardboard, bamboo, and other delicate materials, these puppets are not only works of art but essential components of Paperhand’s large-scale, multidisciplinary performances.

“We lost a lot of tools, a lot of fabric, and a lot of the older puppets we were planning to reuse,” said Zimmerman. “We also lost some of the ones that were going to be in our new show—a show about rivers and the power of water.”

That show, Paperhand’s 25th annual summer performance at Chapel Hill’s Forest Theatre, was just a little over a month away. Entitled The Gift, the show centers on grandmothers and women guardians of waterways, invoking the movement, spirit, and power of water with awe-inspiring puppets that include a 60-foot ocean goddess, a river, and an illuminated whale.

“None of it was lost on us about how close to home it all was,” said Zimmerman.

The storm damage forced both Culture Mill and Paperhand Puppet Project to vacate their long-held studio spaces.

Fortunately for Paperhand, plans for a move were already in the works before Chantal. The communal scale of Paperhand’s art and the number of volunteers necessary to make it—not to mention the archive of past puppets—needed more room. The new space, a warehouse still in Saxapahaw but a bit farther out, was secured, but the move wasn’t to take place until after the big summer show.

Of course, that, like so many things, changed with Chantal.

“The timing couldn’t have been more difficult,” said Heather LaGarde, who serves as president of Paperhand Puppet Project. LaGarde, who owns the Haw River Ballroom, located in the mill’s former dyehouse, is well known for her active role in supporting the arts in Saxapahaw (she and husband Tom LaGarde started the popular Saturdays in Saxapahaw series) and for providing a center for relief efforts after Chantal. (And yes, she’s a friend of this writer—good luck finding an arts reporter in the area who doesn’t know Heather!)

To be able to pivot like that and speak to real climate disaster and resilience, when it has actually completely impacted you and all your work for the whole year, is one of the gifts of art.”

heather lagarde

Paperhand’s move was difficult and rushed, with volunteers and staff evacuating what they could from the old space as quickly as possible so they could get back to working on the new show. And despite the chaos, come August, The Gift took place as planned.

“Watching people reach up for the lit-up whale puppet as they came up the steps of the Forest Theatre was incredible. … Little kids that parents are holding up, older people, teenagers, all had this look of amazement on their faces. … I am just so grateful we were able to keep Paperhand in Saxapahaw—it would have been terrible if the flood had driven them out,” said LaGarde. “To be able to pivot like that and speak to real climate disaster and resilience when it has actually completely impacted you and all your work for the whole year is one of the gifts of art.”

At Culture Mill, meanwhile, the question of real estate became, well, more of a question. Since 2017, the nonprofit has rented its space, using it as a creative laboratory for practices, rehearsals, offices, programs, and artists’ residencies. The building’s dampness, which had always been a concern (“I would tell people the walls cry when it rains,” Swett joked), after the storm felt—and smelled—like it needed major remediation.

For Tommy Noonan, who serves as co-director of Culture Mill with his partner Murielle Elizéon, staying in the space felt like an uphill battle. With climate change, more severe rain and floods would come, and making the building safe would require resources, especially if there was health-hazardous mold, which seemed to be the case. “We can’t ethically practice community care and invite folks into the space—or use it ourselves—if that’s the situation,” said Noonan.

Instead of rushing to find a new space, the organization opted to do what is at the core of their mission: create the conditions for artistic practice by being in the body and the present conditions of a place.

“Even inside of this decision-making, it’s a process-based practice. Instead of jumping into the conclusion, we need to lean into the unknown. We don’t know yet what is coming, but we know what we are committed to,” said Elizéon.

Taking time to decide what the organization most needed to continue its work, which includes several ongoing collaborations with longtime partners such as the American Dance Festival and Carolina Performing Arts, and to secure its future in an increasingly perilous world due to both environmental catastrophe and the defunding of the arts, Culture Mill came to an interesting conclusion: give up a physical space entirely.

“A physical space is not the core of what we are as Culture Mill,” said Noonan. “It’s been an important anchor, a way to anchor our values, but it’s not what we’re based on. … We’re based on the work that we do and our relationships.”

As of December 1, Culture Mill is nomadic. Instead of having a designated space for their work—and their resident artists—they will be operating out of the spaces of their many collaborators.

Being nomadic and working intermittently out of the Haw River Ballroom is, for Culture Mill, a return to the organization’s origins. When the group first began, it had its headquarters in the ballroom. An early project was called “Trust the Bus,” wherein audience members would board a donated, renovated school bus for site-specific music and dance performances at undisclosed locations.

Getting locals to participate was part of the project—and together, artists and audience would share an experience of art and geography that helped join them as a community. The ride sounds not unlike where Culture Mill is now, only instead of trusting the bus, they have to trust the network of support they’ve built around them over the last decade.

“We have always been rooted in the place of Saxapahaw but also in this fluid movement between Saxapahaw and international collaborations—artists coming here, us going elsewhere,” said Noonan. That sense of fluidity, along with the organization’s demonstrated ability to remain flexible in difficult times, will be useful as it moves forward without a fixed address.

Prioritizing people and envisioning relationships as a resource more important than real estate is Culture Mill’s response to Chantal—and cultivating that “community of care” is part of the organization’s work. This fall, they began a new series of workshops that are held at the Haw River Ballroom and focus on building community resilience. The first workshop was entitled “Processing Chantal: Embodied Integration of the Flood.”

As any ecologist can tell you, the health of one ecosystem impacts the ones around it—and that sort of interconnectedness has long been part of life in Saxapahaw.

The folks at Culture Mill often use the word “ecosystem” to describe the work they do, envisioning their role to be that of a mill (hence the name), operating with a circular exchange of bringing in many components—people, ideas, resources, and energy—and then sharing them. Art, as they see it, isn’t a linear transaction but rather a relational one grounded in the community that creates it.

To cover the costs incurred from the storm’s damage and the unplanned move, Paperhand created a GoFundMe campaign to raise $100,000 and was able to make that goal. Even though community support swelled during storm recovery, LaGarde, who sits on the board of directors for Culture Mill as well as Paperhand, is worried that both organizations will have a difficult year ahead of them. Storm recovery aside, all arts organizations and nonprofits are feeling the economic pinch of the federal government’s massive cuts.

“With Paperhand, it feels like, OK, they’re in a space, they’re safe … they’ve had to adjust, and there’s been a lot going on, but it should work out for the best. With Culture Mill, it’s still unknown where or how they will land,” LaGarde said. ”They are having to navigate these waters very differently.”

Navigating the waters is something we all have to get better at—it’s a necessary skill beyond arts nonprofits in river towns.

After Chantal, the N.C. State Climate Office at North Carolina State University published an account of the storm activity that ends with this sentence: “Climatology tells us that the Coastal Plain is a common target for hurricanes, and after last fall’s hard hit from Hurricane Helene in the Mountains and Chantal’s heavy rain and flooding in the Piedmont and Sandhills, it’s clearer now than ever that nowhere in the state is immune to tropical impacts.”

Nowhere in the state is immune, and if you haven’t already been affected by a storm, you probably will be soon. Resilience is the ability to adapt to adversity, but what is recovery? Is it simply a matter of repairing old buildings and putting people back in them, or is it recognizing that the landscapes around us have irrecoverably changed, and maybe we need to do things differently?

For both Culture Mill and Paperhand Puppet Project, Chantal’s destruction of their physical space brought hardship along with complex feelings of grief and uncertainty, and renewed appreciation for the safety and support of their community. It wasn’t about reassembling to re-create what existed before, or throwing out a few puppets and moving on, but instead has become an ongoing opportunity to grow and change in new ways.

“We are left feeling strong and supported and held by our community here—and that’s a good place to move from when you’re doing art on a communal scale like this,” Zimmerman said. “Before the flood, we had more than 300 volunteers come by the studio to help papier-mâché and sew and do other projects. I see that number only increasing as we go forward in the new space.”

Ultimately, Zimmerman said, he came to view the experience as “the river sort of reaching up and teaching us.”

“Teaching us a hard lesson, but a powerful one,” he continued, “that letting go is just a part of the journey.”

To comment on this story, email [email protected].

Source link