The call came at night in early December: Chatham County Schools would be closed the next day due to a forecast of snow. In Pittsboro, Jessie Mewshaw went into action. “First, it’s the conversation with my spouse: ‘Can you stay with them? No, you can’t, you have to go.’” Mewshaw spent the next hour canceling all her clients for the next day.

Mewshaw is a speech therapist who works primarily with autistic children and teens. Because she’s paid by the session, she loses about $500 per day when she has to cancel. She also worries about her clients when school and therapy routines are disrupted.

“No matter what an amazing caregiver you are, that’s going to take a toll on your nervous system,” Mewshaw said. “Neurodivergent kids feel those changes. When you are frazzled, they are now frazzled.”

In the end, 0.1 inch of snow fell, according to the National Weather Service’s Raleigh office. Chatham County Schools said in a Facebook post that evening that although the county did not fall within the official winter weather advisory area, they were still calling for a two-hour delay the next day due to “a slight chance” of black ice in the morning.

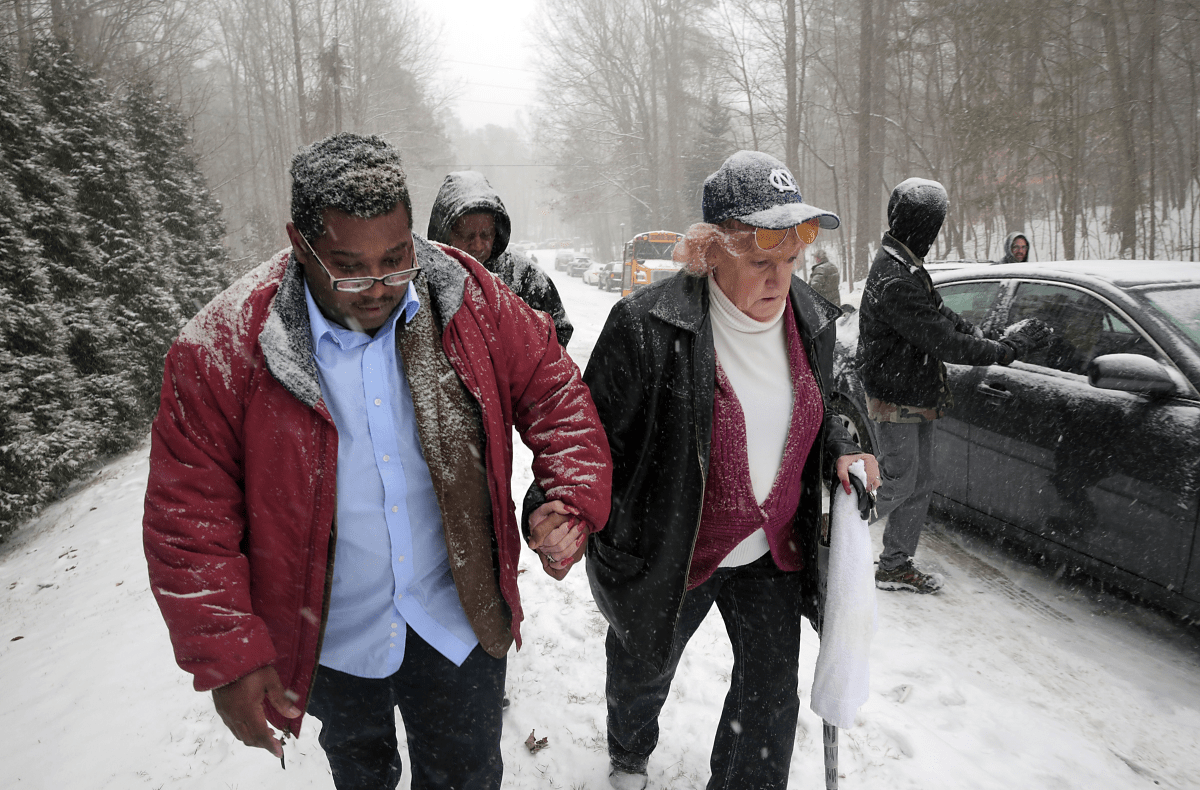

A winter storm put school on ice for parts of the state this week, and another is forecast for this weekend. But snow has long been rare in most of North Carolina, lending every dusting a mythic excitement. For school-aged kids, these days mean snow angels, movies, and hot cocoa.

At least that’s the nostalgic snow day memory. With climate change, snowfall has decreased significantly over the past 50 years. According to the North Carolina State Climate Office, Raleigh’s average annual snowfall dropped from 8 inches between 1961 and 1990 to 5.1 inches in the last three decades, a 36% dip. Other locations around the state saw decreases of more than 50%.

In Forsyth County, days with wintry precipitation fell by about a third over that period, based on National Weather Service numbers from three data collection points in the county. (The tally includes snow and sleet, but not freezing rain, which is difficult to distill from historical data.) But the number of school closures due to winter weather was roughly the same over those 60 years, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools data show.

Six other school districts The Assembly contacted didn’t maintain records dating back that far, and neither does the state Department of Public Instruction. Still, teachers and administrators across the state said in interviews that they believe their districts have become more likely to delay or cancel school.

At the same time, more families have dual-earning parents now. Fewer than half of married couples in the 1960s had two working spouses, compared with about 65% in 2010.

Taken together, this has changed the quintessential snow day—instead of snow, cold and rain; instead of movies, remote learning; instead of hot cocoa, parents glued to laptops, still attempting to do their jobs.

There are lots of reasons for school systems to be cautious, including large districts where bad weather can have different effects in rural and urban areas, bus driver shortages, and painful memories of bad calls in years past.

Finding a solution that works for everyone is “a little bit of a rabbit hole,” said Mathew Palmer, project director of N.C. State University’s School & Community-Aligned Master Planning (SchoolCAMP), which advises school districts on complex problems. “I’ll forewarn you because I’ve been down it a couple hundred times. There’s reasonable positions to take across the spectrum of the topic.”

Meanwhile, many families struggle when schools close. “Schools are a site for more than just learning,” said Jennifer Erausquin, associate professor of public health education at UNC Greensboro. “They provide nutrition, they’re sometimes a site for mental health counseling, and particularly in the younger grades, after-school care is super important.”

After a string of three weather-related closures in December, Marelle Cacciabaudo, an instructional assistant at Lyons Farm Elementary in Durham, asked a kindergartner whether he enjoyed his time at home.

“He gave me a thumbs down. And I’m like, ‘Oh, buddy, what’s wrong? You didn’t get to have any fun?’ And he’s like, ‘No, I wanted to be at school.’”

School is “one of his safe places,” Cacciabaudo said. “And it was just so heartbreaking to me.”

Sunny and 43 Degrees

The fact that school closures have held steady even as snowy days decreased comes as no surprise to those with experience making such decisions. Chris Blice, assistant superintendent of operations at Chatham County Schools, said when he started in education 45 years ago, “the idea that we would send students home or cancel after-school events was kind of a nonexistent thing.”

Several factors have converged to make administrators more likely to close schools due to wintry weather.

In 2005, a surprise inch of snow turned to ice on roads in Wake County, causing gridlock that prevented buses and parents from picking up children. About 3,000 students were trapped at their schools overnight.

“The memory of that,” Blice said, “is pretty strong in a lot of people’s minds.”

Blice also says that families have pushed harder for school districts to make school closure calls the night before. But it can be hard to predict what the roads will look like that far in advance. On a typical day with snow potential, “the temperature is anywhere around 30 to 35, hovering around that critical value,” said Jonathan Blaes, meteorologist-in-charge at the National Weather Service in Raleigh.

With less precise data and pressure to make earlier calls, administrators tend to err on the side of caution.

“The worst days are when it’s like, you make a call and then it’s sunny and 43 degrees,” Palmer said, referring to his previous job as senior executive director of operational services for Durham Public Schools. “Parents are saying, ‘What? Who made this decision?’ And you’ve got to own it.”

A shortage of transportation workers has further narrowed the margin of error for many school districts. Relatively low pay leaves many bus drivers—as well as teachers, nutrition workers, custodians, and other staff—residing outside the area where they work. Even if conditions are viable in a school district, workers may not be able to commute safely.

For frustrated parents, the solution to North Carolina’s snow woes can appear simple: Buy more plows and pretreat the roads more thoroughly. North Carolina’s Department of Transportation (NCDOT) has an annual budget of $60 million for storm preparation and snow and ice. During wintry weather, the department uses 1,250 dump trucks to plow and spread salt and sand, typically starting with priority routes like interstates and four-lane highways and then moving to secondary roads. The department said its budget has grown over time but has “remained steady in recent years.”

“Between NCDOT staff and our contracting partners, we feel we have adequate resources to address typical weather events,” NCDOT spokesperson Jordan Campos said. Still, with shaded rural areas and frequent black ice—which the department noted is dangerous for its vehicles, too—the department often can’t get backroads cleared quickly enough to avoid school closures.

“In planning, we have these things that are called wicked problems,” Palmer said. “Good people dedicate all of their thinking lives to solving them but never do. I’d say we’re in that space right there.”

‘A Rain Dance Somewhere’

Retha Daniel-Ruth’s mornings start at 4 a.m. Her first busload of students enters Southwest Elementary at 7:15 am, but Daniel-Ruth has them in the parking lot by 7, “so that if they need to decompress, they can. Just so they can be happy for a few minutes before they go in.”

Daniel-Ruth has been driving for Durham Public Schools for 32 years. She knows all her students by name, and she’s driven for many of the same families for more than 10 years. She’s seen it all: ice, snow, flooding, and even tornadoes. As of this story’s publication, Durham hadn’t responded to a request for data on school closures over time, but Daniel-Ruth thinks they close much more often than they used to for inclement weather, and she appreciates the prioritization of safety. But she worries about staff who lose money when school buses don’t run.

When Durham schools closed for three days of wintry weather in December 2025, Daniel-Ruth and other staff who are paid hourly, rather than salaried, had the option of completing a series of online modules in exchange for a day of pay. For the other two days, staff with accrued paid time could use that to receive pay; newer staff without that time weren’t paid for the days off.

Even salaried teachers can be affected. During those same closures in Durham, Jessie Schmitz, who teaches English as a Second Language at Riverside High School, said she was instructed not to work remotely but to take paid sick days. (Schmitz and Cacciabaudo said principals in the district give teachers differing instructions on days with no school. DPS didn’t respond to a request for comment.) Though not ideal—like most teachers, she had plenty of work she could have done from home—Schmitz had accrued plenty of time off in seven years of teaching.

But “talking to some beginning teachers who have almost no sick days,” Schmitz said, “they’re freaking out. They’re like, ‘I used up two of my three sick days! What happens if I actually get the flu?’”

In Asheville, Hurricane Helene served as an impetus for public school workers to seek better inclement weather policies. In December 2025, the Asheville City Association of Educators secured the right for all staff to telework on inclement weather days, hazard pay for essential staff asked to report to work, and an earlier call time for school closures.

“We unfortunately know what inclement weather looks like,” said Carson Bridges, the association’s president and a first-grade teacher at Claxton Elementary. “It actually ended up being the No. 1 priority for everyone … making sure that, even if it’s a couple days of snow and ice, all of our people are being taken care of.”

The Durham Association of Educators is also pushing for better inclement weather protections for classified staff.

“We didn’t tell it to snow,” Daniel-Ruth said. “Somebody might have been doing a rain dance somewhere, but it wasn’t me.”

Rough Sledding

For parents, the snow day problem remains.

Carrie Blanchard of Pittsboro used to run North Carolina’s COVID-19 immunization program as the director of the state’s Department of Health and Human Services Immunization Branch. She took a remote job in the pharmaceutical industry to better juggle her responsibilities as the sole parent of two young children.

Blanchard has a steady salary, but she rarely has enough sick days to cover daycare closures. “I feel like I’m letting everybody down,” Blanchard said. “I’m not able to be the best, most present parent because I’m trying to multitask with my kids at home, and I’m not a good team member at work because I’m trying to work and take care of my dependent children.”

Kendred Mills and his family rent a townhouse in Greensboro, less than a half-mile from their children’s elementary school. The distance is easily walkable even in wintry conditions, making school closures frustrating. Because he and his partner both work in-person hourly jobs, they take turns calling out to stay home with the kids.

But finances become difficult in seasons with many closures—like January 2025, when between delayed starts, early dismissals, remote learning days, and teacher workdays, Guilford County Schools held only nine full days of school.

“We’ve gotten backed up on bills more than once,” Mills said.

And parenting stress can take a significant toll on children’s mental health, said Dr. Rachel Riskind, a social developmental psychologist and professor emerita at Guilford College. “It’s one thing to have a one-off snow day. It’s another thing to feel like up is down and left is right and you never know what to expect in a given week.”

In an ideal world, employers would grant parents flexible leave, meteorology would anticipate wintry precipitation down to the second, and North Carolina’s road-clearing capabilities would rival New England’s. In the meantime, parents and teachers floated a range of solutions.

Cacciabaudo proposed that, as an instructional assistant, she could staff a neighborhood community center to give some kids a place to go when Durham schools can’t open. Blanchard wondered aloud whether communities could organize to support each other so that solo parents like her don’t have to do everything alone.

In the meantime, school closures continue, sometimes for trace amounts of wintry weather and sometimes, like this week, for actual ice storms. “These are the real emergencies,” Mewshaw said before the storm hit.

She and her family had carefully prepped the generator, flashlights, camping stove, and charging station. They were grateful not to lose power. The first days home from school were fun, but by midweek, Mewshaw had to hire a babysitter so she could go back to work. With most roads in the county appearing clear, “it feels really excessive to have them out of school yet again,” she said.

Chatham County Schools remained closed Thursday and announced they would open after a two-hour delay on Friday.