Near Luxor in the Nile valley, quite far away in space and time, there is a place once named City of the Dazzling Aten which contains an array of fine serpentine walls. These walls curve left and right in an even rhythm as they wrap dense clusters of mud and stone buildings.

Though attractive to the eye, these walls were probably not designed for their looks; they were designed to save bricks. The snakelike profile creates a clever self-supporting effect, so that the wall constantly leans into itself as it progresses in a series of connected, alternating arches. The efficiency of the shape allows the wall to be just one brick (or wythe) thick, while a normal, straight wall of the same strength and length would need to be two or three bricks wide with the insertion of piers or reinforcing columns at regular intervals.

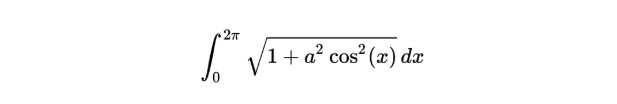

The extra length of the serpentine design is more than paid for by the savings in thickness, resulting in a budgetary gain of 40-50% according to a certain integral expression…

…where “a” is the height of the wave from the centerline of the curve, and the resulting calculation gives the total length of the wall. I show this not because I understand the math, but because I am amused that the symbol used to indicate the material calculation (which shows how much more economical the serpentine style is in relation to the straight style) is drawn with two gently opposing curves. A good moment to remember that nature rarely brings along straight lines for her serious engineering adventures.

Good ideas tend to travel far and wythe, or else they get reinvented. On this side of the globe, architect-President Thomas Jefferson was likewise fond of efficiency, so he adopted the serpentine wall for his campus design at the University of Virginia. Just one brick thick, it was built around 1822 and is still holding up nicely.

We sense here a sort of mathematical poetry, called corrugation generally, taking the form of a wave profile which maximizes strength and rigidity while minimizing the use of precious materials. This poetry is recited with enthusiasm in unexpected places. The cardboard box which arrived yesterday from Amazon is a masterpiece of corrugation, and so is this solitary silo – one of thousands across the midwest – as it sits with dignified splendor amongst the corn fields:

What a dreamlike assembly to stumble upon at seventy-five miles per hour on a brisk winter morning! It is a Cape Canaveral, amusement park, and military tent all fused into one mysterious metal conglomeration. It is in one glance both impossible and unavoidable, absurd and industrial, abstract and literal, monumental and invisible.

An hourglass (each arriving truck, in turn, becomes the bottom half of the device) is the central and organizing shape in this small grey village, guiding vast sums of precious material down to the tip of a cone, a chute, a downward sliding delivery from general (silo) to particular (farmer). The harvest of a crop is here mechanically organized in such a way as to facilitate the growth of a herd, pushing energy up a chain towards denser, more concentrated kinds of protein and more efficient transformations of energy. (Every building might be imagined as a kind of silo, or simple distribution machine, meant to assist with a vital transformation of energy from lower to higher forms.)

You may notice that the dominant structural theme is essentially Egyptian, if not older, taking the shape of corrugated metal panels providing skin and structure simultaneously for the silos.

These containers rely on the same familiar serpentine profile to give strength, rigidity, flexibility and durability to their volumes with a minimum expenditure of galvanized steel. This is the same pragmatism, ambitiousness and frugality which was discovered by archaeologists at the City of the Dazzling Aten. In the lower left corner above you will see what fills these capped cylinders: large amounts of feed corn. Since it had already spilled, I scooped up a pocketful of golden nuggets from the frozen dirt.

Jon Calame teaches art history at the Maine College of Art and Design and the University of Southern Maine. This column is supported by The Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.