A Lockport resident’s role in bringing about societal reform in the United States is getting a public boost thanks to the efforts of a New Lenox researcher.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Lockport had become a fulcrum point for abolitionists, according to Lindsey Minas, who recently graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history from Lewis University in Joliet and is pursuing graduate studies at the University of Chicago.

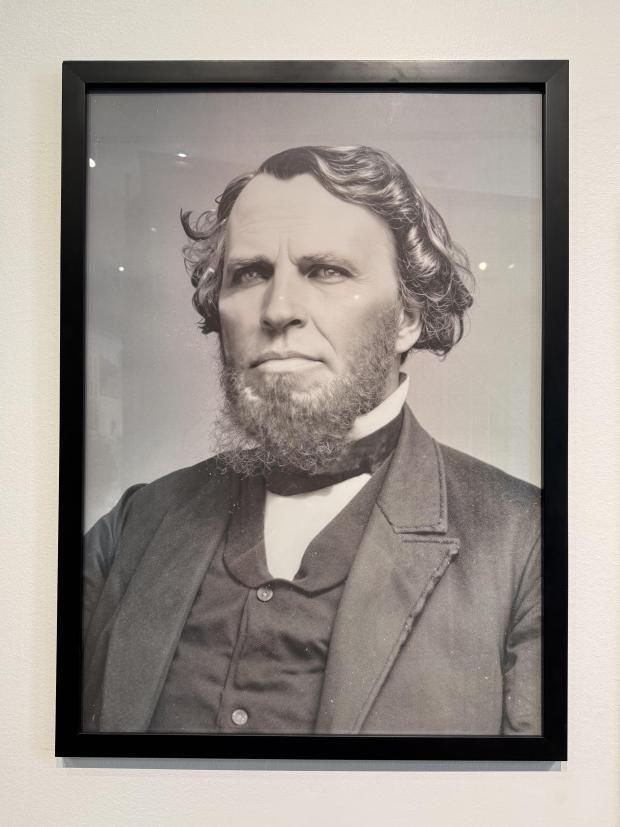

Among the mid-19th century activists drawn there was Ichabod Codding, a Congregationalist minister who some say influenced President Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator.

“Lincoln had only aspired to limit the spread of slavery — not end it altogether,” Minas said. “Codding wanted Lincoln to deep dive into the abolitionist movement. While there was some hesitation, we know that later he does. So, it’s easy to assume there was some sway on Codding’s part there.”

Minas’ local research efforts have yielded a Story Wall exhibit about Codding now on display at the Gaylord Building, 200 W. 8th Street in Lockport.

Also at that location, Minas will also deliver a Think & Drink lecture about Codding at 7 p.m., Thursday, Feb. 12, following an introduction by Larry McClellan, president of the Midwest Underground Railroad Network.

Prior to running for a senate seat, Lincoln, a Whig, was unwilling to fully commit himself to the cause of the Republican Party, an organization born out of a desire to eliminate slavery. But then someone gave him a nudge.

In an 1854 letter to Codding, Lincoln railed about having been involuntarily signed on to serve on the Republican State Central Committee. Codding and several abolitionists living in Illinois at the time played key roles nurturing the fledgling Republican Party.

“While I have pen in hand, allow me to say I have been perplexed some to understand why my name was placed on that committee,” Lincoln wrote. “I was not consulted on the subject; nor was I apprized of the appointment, until I discovered it by accident two or three weeks afterwards.”

Lincoln also complained that Codding’s written invitation to attend the related committee meeting in Chicago didn’t arrive until the day of the event, when Lincoln was out of town.

That wasn’t the only time Codding pushed personal boundaries to drum up interest in the abolitionist movement.

A member and frequent lecturer at the Congregationalist Church, 231 9th Street in Lockport, Codding once organized an anti-slavery rally there without asking permission and while the pastor was out of town.

Tricky business aside, “He had an ability to change minds and sway crowds,” Minas said.

And indeed, Lincoln did come around, as a Republican candidate for the Senate in 1858.

Lincoln also publicly opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which aimed to expand slavery to additional states. During the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates, he challenged the incumbent Democratic senator who introduced the legislation, Stephen Douglas.

Minas said she believes Codding, who was as known locally as “the great orator,” may even have influenced Lincoln’s eloquence.

Upon accepting the Republican nomination for senator, Lincoln delivered his much-admired “House Divided” speech, saying, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.”

On the matter of slavery, Codding also did more than just talk.

“He personally assisted enslaved people,” Minas said, adding that he once delivered freedom seekers to the home of abolitionists living in Gooding’s Grove in Homer Glen. Those abolitionists helped the freedom seekers travel onward toward Canada.

Minas said she discovered Codding after hearing a MURN lecture by McClellan.

“I knew a little, but until I heard Dr. McClellan’s talk, I didn’t know how rich the (abolitionist) movement was here, especially in towns so close by.”

Minas approached McClellan, a Governors State emeritus professor of sociology and community studies, for guidance and a possible internship. Soon after, she started researching local connections to Codding, one several abolitionists profiled in McClellan’s book, “Onward to Chicago.”

“I chose Codding because I was impressed by how close he was to where I am and because he’s so generally unknown,” said Minas. “Codding was so unlike anyone I learned about in high school, and I wanted to bring that to light.”

Codding grew up in New York and attended Middlebury College in Vermont. Early on he caused a stir delivering anti-slavery speeches and writing pamphlets.

So deep was his passion as a student — and so averse was the school to his “radical” views, as some sources say — he left his studies to represent the American Anti-Slavery Society. His first post was in Maine. He eventually moved on to Illinois and Wisconsin.

Codding came to the Midwest in 1842, six years before the opening of the I & M Canal. The massive construction project was intended to connect water-born commerce coming from the eastern United States by way of Chicago and the St. Lawrence Seaway to America’s Deep South and the Western frontier via the Illinois and Mississippi rivers.

Like other abolitionists anticipating slavery’s spread with westward expansion, Codding was drawn to Lockport, a key location linking the nation.

Canal commissioners constructed the Gaylord Building as a warehouse to help facilitate the canal project. As ground zero, Lockport attracted numerous engineers, speculators, investors, laborers and their families.

“Codding represents a larger group of people who were outspoken about what this (the abolishment of slavery) means and how a movement came to be in the Midwest,” Minas said.

Enlisting the help of Congregationalist Church historians and members of the Lockport Genealogical & Historical Society, Minas was able to verify Codding’s ties to fellow Illinois abolitionists.

Codding joined his mother and sister Sabrina Mason, who moved to Lockport to be with the Mason family. The Masons were members of the Congregational Church where Codding lectured. Hale Mason was an abolitionist.

Codding also worked with an abolitionist member of the Preston family. He married Hannah Maria Preston. She wrote Codding’s autobiography.

Codding eventually moved away from Lockport and became a pastor at a Unitarian Church in Baraboo, Wisconsin, where he later died.

His body was returned to Lockport Cemetery, where a tombstone identifies him as “A fearless apostle of freedom for the slave, and in religion.”

Minas along with Lockport resident Kelly McCleod recently applied for Codding’s gravestone and the Lockport Cemetery to be recognized as part of the National Park Service’s National Network to Freedom. The network promotes the history of resistance to enslavement through historic sites having verifiable connections to the Underground Railroad.

Susan DeGrane is a freelance reporter for the Daily Southtown.